I wrote this piece in maybe 2018. And I didn't dare share it, till today.

Read it to find out why.

1. If you’re good, you’re probably full of doubts

2. Imposter syndrome exists because you are in fact an imposter,

or at the very least affecting the social order. It is very real.

Stress ∝ Skill, Ability

If you went to a super nerdy school like I did, you know this person who is the most annoying of them all: “oh my god, I’m freaking out. Like freaking out. Like I can’t breathe”. Their grade comes back. Perfect score.

I’ve been that person. Sorry to everyone who knew me. I’ve also rocked up to an exam without having studied anything at all, and somehow I wasn't stressed for that one. I knew I wouldn't do well, and I didn't.

But like, there wasn't anything to stress about there.

I didn't have a fighting chance, but I already knew that.

It's when we have the potential to do well, I think, and when we've really poured our heart and soul into something, when we get stressed. Because it's really heartbreaking to really try, and then find out you're still not good enough.

I feel like this lesson got pretty well imprinted on my brain after my years in my super-nerdy school, that I only really get stressed about exams where I really studied, and gave it my all.

If you've ever watched competition-based reality TV shows, you may have observed this there. The person who is the most worried about doing well, often comes out on top – and no one is more shocked or surprised than they themselves are. This may come across as disingenuous sometimes because the audience has seen their high level of performance throughout the competition – and somehow they still seem to be the last to know.

On the flipside, the most arrogant competitor somehow ends up having a 'mishap' or some misfortune which lands them in the bottom – through no fault of their own of course...

This demonstrates my first point: people who are skilled are filled with doubts, and people who are not are overly confident.

It's About a –Specific Skill–

baking • singing • dancing • marketing • coding

Just to clarify, this doesn't place people in two categories, "smart, capable people who underestimate their skill or ability" vs "losers who think they know it all".

We can be good in one specific activity and be an expert in that, yet know nothing about something else entirely. It wouldn't surprise me that if all of us fall into both categories depending on what the subject is.

That doesn't make this phenomenon any less real. We often underestimate how complicated or nuanced something we don’t know is.

Why the Unskilled Are Unaware

I cannot recommend watching this video produced by Ted-ed enough. It's literally the tl;dr version of a landmark paper released by a team of researchers titled "Why the unskilled are unaware" which opens with this line:

"People are typically overly optimistic when evaluating the quality of their performance on social and intellectual tasks.

In particular, poor performers grossly overestimate their performances because their incompetence deprives them of the skills needed to recognize their deficits"

– read the paper in full here

This video explains really well that the more we dive into a subject, the better idea we get at the scope of the topic. And often, it’s overwhelming.

Knowing What You Do Know

it's about to get meta

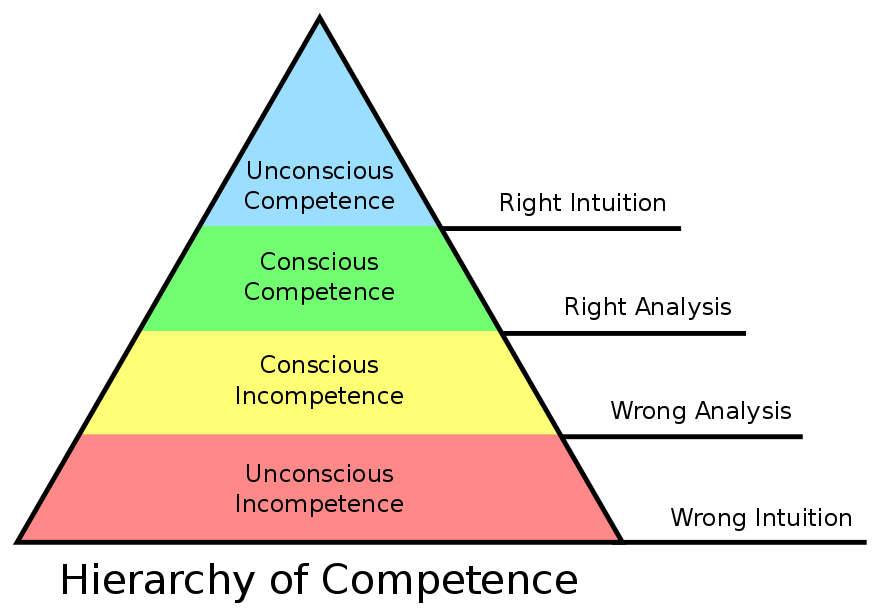

It’s the difference between not knowing what you don’t know, and understanding how much you don’t know. And that’s a big difference. The difference here is in the awareness of one’s own skill. Being unskilled and unaware of it, is a double-curse of sorts because your very ability to judge your skill is also lacking.

As the video describes the incompetent:

First, they make mistakes and reach poor decisions. But second, those same knowledge gaps also prevent them from catching their errors. In other words, poor performers lack the very expertise needed to recognize how badly they're doing.

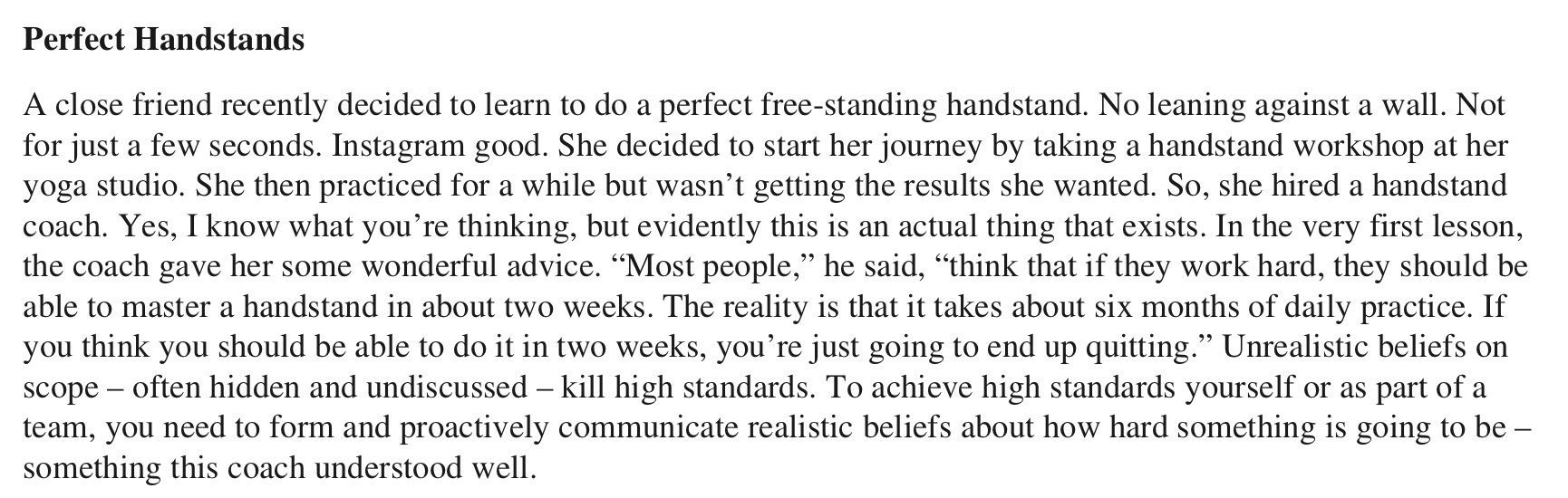

Jeff Bezos passed this note with his team about how severely we underestimate the lengths we need to go through to acquire a skill, any skill – in this case, a handstand.

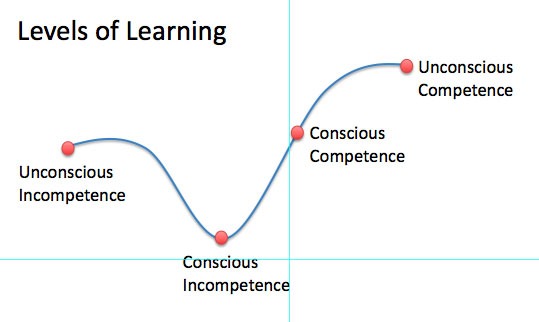

If only the process of learning something would be as smooth as the graph above where know when you're moving from unskilled and unaware to at least reaching the self-awareness to understand your incompetence.

There should be a word for this ‘click’ that happens; when you go from unskilled and unaware, to reaching the self-awareness to understand your own incompetence. But when you’re still in the don’t-know-anything-zone, we call it the Dunning-Kruger effect.

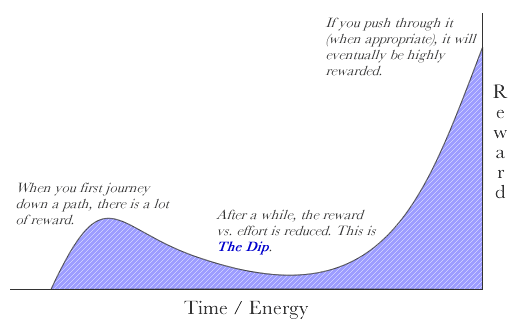

The reality is after we first start learning it's fun at first, and then it becomes super frustrating. Many people give up at that point. This is why a lot of people know a couple of chords on the guitar but not much else, a handful of phrases in another language, but can't hold a conversation etcetera. There's nothing wrong with stopping to learn at this frustrating point, and the likes of Seth Godin even encourages it in his short and to-the-point publication, The Dip.

But there's a second moment that happens, when you cross the line from conscious to unconscious competence, meaning you know what you're doing so well you don't even realise you're doing it. It's become muscle-memory. But we don't notice it.

Learning is gradual and is such a journey of frustration and small wins and chaos that it can be really hard to internalise how far you’ve come. Because most things are not as cut and dry as “being able to do an Instagram worthy handstand”.

Because no matter how good you are, you’ll never know everything. But because by now you have a good grasp of the subject, you’re glaringly aware of your knowledge gaps. It’s easy to underestimate how much time you may have sunk into casual googling and conversations and simple time spent thinking about something.

Having this deep understanding of something often means it all just seems obvious. And not just obvious to you, simply obvious in general. If you’ve ever had an old science teacher who becomes frustrated at the class for not picking up what they're putting down, you know what I mean. They don’t even comprehend how to get on your level to start explaining something so basic, because it all seems so trivial to them. My chemistry teacher was like that. He just didn’t grasp how chemical reactions weren’t intuitive to us, the first time we heard about them.

Another example would be from my sector, the tech industry. It’s not uncommon that those technically minded spin marketing, social media management, PR, and even design and product (cos why not) all into ‘marketing’. The stories I’ve heard of some tech business expecting ‘a marketing intern’ to execute all of these varied fields during their 6-week stint would be hilarious if it wasn’t also so condescending. I know, because I’ve been there.

This shows their unconscious incompetence of “the business side” because actual marketers would say “oh, I don’t do PR – hire someone else for that”, and the other ways around – because they are not all the same thing. Which demonstrates expertise in the field actually, because marketing is not design which is not social media marketing which is not PR.

This leads us to the second brain-breaker when it comes to our abilities and our ability to perceive our own abilities accurately: “the exceptionally competent don't perceive how unusual their abilities are".

If you’ve ever worked with programmers and complimented them on their excellent work who don’t smile and say thank you but instead just look very sheepish because they “just googled it”, you’ve witnessed an expert at work.

Well, what exactly was it that they googled? We all know that Google has all the answers – but we can only extract the relevant information when we know what questions to ask. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where your knowledge of something is so limited you don’t even know what to put in the Google machine?

That’s the difference.

Because we don’t remember and therefore don’t recognise the time we’ve spent on mastering something, and how the journey wasn’t linear, and there wasn’t necessarily one big a-ha moment we can recall, but it’s like a boiling frog situation where we have developed an understanding of something so thoroughly that it just makes sense to us – it can be really difficult to zoom out and try to remember what the general baseline is.

Most of our lives are not a sport, where milestones like “you’ve made it on the national team” are more definitive. When are you a world-class project manager? Or childminder? Or artist? It’s hard to tell, because there aren’t necessarily clear milestones along the way.

Have you ever tried to pass on one of your enviable skills to someone else? You may realise you’re talking in much more basic terms than the level you normally operate at.

One of my favourite things to talk with people about is strategy, particularly online marketing strategies. My experience however, is I often end-up as tech support for Facebook. I wouldn’t even consider ‘navigating the Facebook interface’ a skill. But trust me, it is – particularly when it comes to boosted advertisements and targeted audiences. I spent like a year explaining to people the difference between a Facebook profile and a Facebook page. That’s not even starting to talk about what the advertisement or brand should be about, or when to share it.

This actually is a form of imposter syndrome, when you discount your own knowledge to be ‘assumed general knowledge’. Where do you calibrate the ‘assumed general knowledge’ line? That’s a really hard question, and depends 100% on who you’re talking to. You’d be surprised how often you’d need to clarify concepts, define the vocabulary used, and provide context. It’s like the establishing shots in movies. People need to know the where and the when before they can take in your message.

Not to mention how people’s idea of success can widely vary.

I’ve been aware of the ‘big level’ imposter syndrome for a while. But these subtle giveaways to imposter syndrome are prevalent as well, and I’m lucky enough to have friends who point out to me when I do it. I hadn't recognised them in the smaller day-to-day communication ways. The way in which everything *I* as a person know, seems obvious and therefore not so valuable. I certainly have forgotten the hours sunk into trying to see how things fit together. It’s weird, because as soon as something clicks, something makes sense to us, it no longer plays on our mind. So we disregard it. It becomes so obvious to us, we think it’s obvious to everyone. Even if it took us months, years even, to get there.

Experts don’t make the mistake of not recognising how much they know. The mistake they make is overestimating how much everyone else knows, therefore devaluing their entire domain of expertise.

I just want to clarify, just because we may be experts in one area or field, it doesn’t make us "an expert", period. Just because you know a whole lot about one thing, as soon as you cross the line into a different field even just a little – you are back to not knowing anything.

And if you think to yourself –well, I’m smart, how hard can it be?– I sure hope you’ve been paying attention, because then you’d know exactly where you’ve found yourself. Straight back at the bottom of the pyramid, a level we like to call unconscious incompetence. In short, you don't know jack. And you don’t even realise.

This is actually why doctors famously lose a lot of money in the stock market. They figure they’re smart, how hard can it be, and invest from the glory of the Dunning-Kruger zone. This is possibly the only scenario in the world where literally everyone is on the side of the bankers because no one likes condescending arrogance.

– The New Yorker

The relationship between how much you know and how much you don't has a reverse impact on how much you think you know.

- If you don't know anything; "ah, how hard can it be"

=> Often displayed as confidence. Arrogance even. - If you already know a lot; "oh man, there's so much I don't understand fully yet”

=> I don’t know if I’m the best person to ask

The time spent asking "how on Earth do these pieces fit together...." and googling and researching and spreadsheeting and writing until finally something clicks, forgotten.

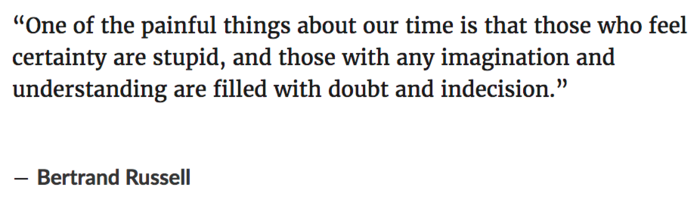

Those able doubt and those not so able display confidence.

Bertrand Russell was born in 1872. This is not a new phenomenon.

It’s also real. Have you ever been deep in imposter syndrome land, full of doubts about yourself, your ability, your place, your motives, your outfit, your everything – and then suddenly someone comes along, and questions you?

Well, I’m sure you have. This is why job interviews and applications and networking and sharing creative work online and moving to a new place etcetera is really scary and overwhelming. Not only do we feel completely incompetent, but now we have to demonstrate how we’re not. Oh and don’t worry, all that is at stake is everything. Your name, your reputation, your livelihood.

How often have I had some IRL reddit nerd mansplain to me that the business I’m in doesn’t make sense? It’s intimidating as fuck. More often than I can tell you, and it took me years to figure out the language to deal with these trolls, who think just because they know how to code, they suddenly understand the business model of the live entertainment industry. Bro, just no.

Or have you ever had someone just flat out devalue the worth of all of your skills in an instant, even after they recognised it?

From the video (paraphrased): “oh hey there intern. You just saved my company. Now go get me a coffee.”

We laugh, cos it’s true.

And fuuukd.

And that comes from the privileged standpoint of those of us even able to get fancy job interviews or move to the big city.

"Getting" to go on that coffee-run is already placing you in the more privileged half. And then what about those who are the only woman in a boardroom? The only person of color in a classroom? The only gay in the village? A kid from Sweden who is really good at ‘volume control’?

Critics accused him of doing nothing on stage but fiddling with the volume on prerecorded playlists, otherwise just jiggling and smiling.

How was that difficult?He admitted to Jessica Pressler of GQ magazine that yes, volume control was a lot of it. And yes, the playlist was planned, not adjusted moment by moment in the old style. He then scrambled to defend his art, explaining how carefully he had to work out beforehand how to build up energy in a set, how to fade expertly out and in, how to keep the crowd so into it that they wouldn’t, couldn’t leave.

– from The Economist "Avicii (Tim Bergling) died on April 20th"

You feel like an imposter, because you are an imposter. You are affecting the social order. If you don’t want to do that, you’re out of luck. This is why gays move out of their villages, and why both black people and women have movements around them. Celebrities have mental health problems. Very often the options are to suffer, leave, or fight. Or any combination of the three.

But this applies wider as well. Just because someone doesn’t have an obvious "minority identity" doesn’t make their imposter syndrome any less real. Maybe they’re overcoming addiction. Maybe they were raised in an abusive household. Maybe they have a serious mental health condition. Maybe they’re from a farm, or a trailer. Maybe they don’t have ‘the right’ education. Maybe they have no education. And maybe they’re just some normal kid who can’t believe they’ve worked themselves up to the situation they’ve just found themselves in.

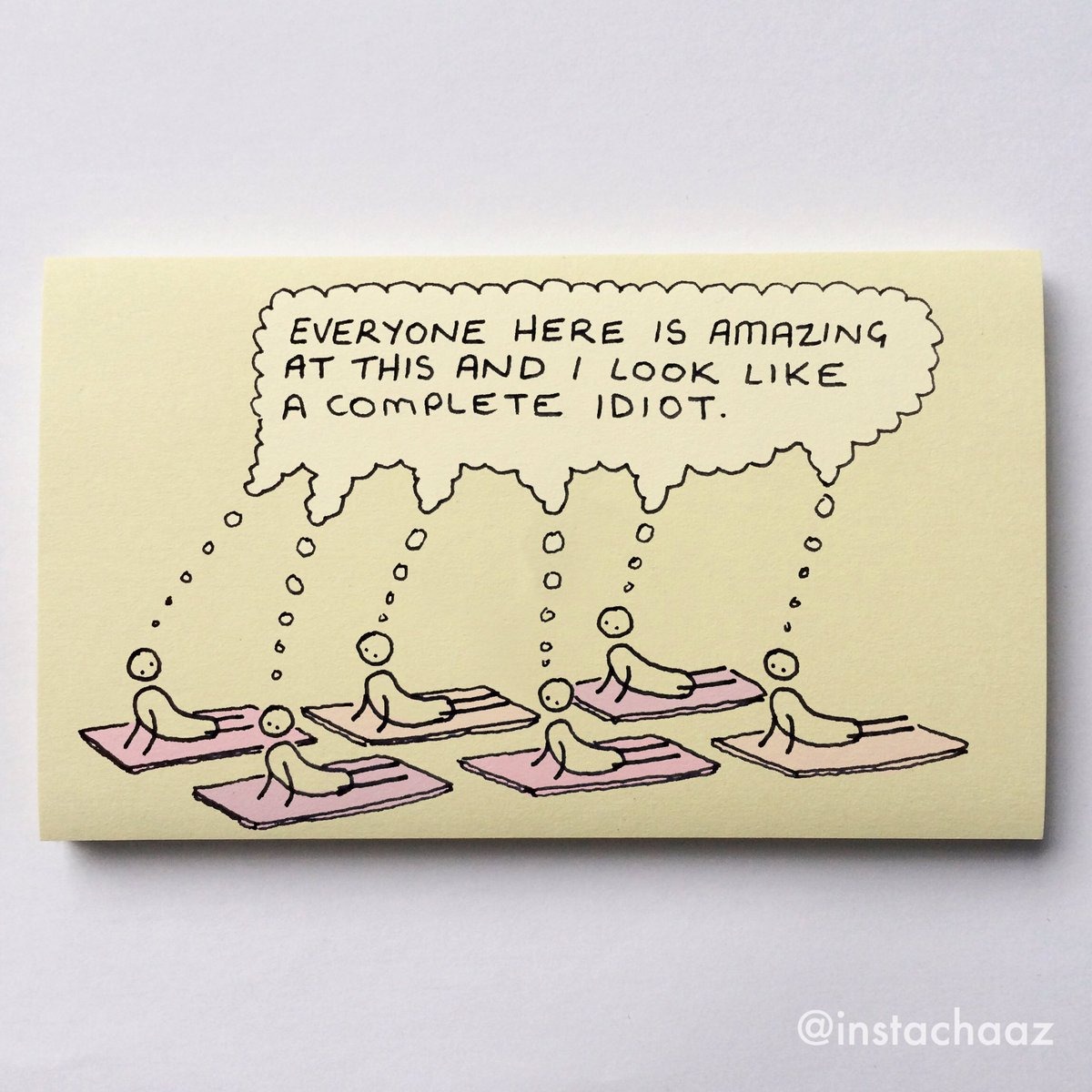

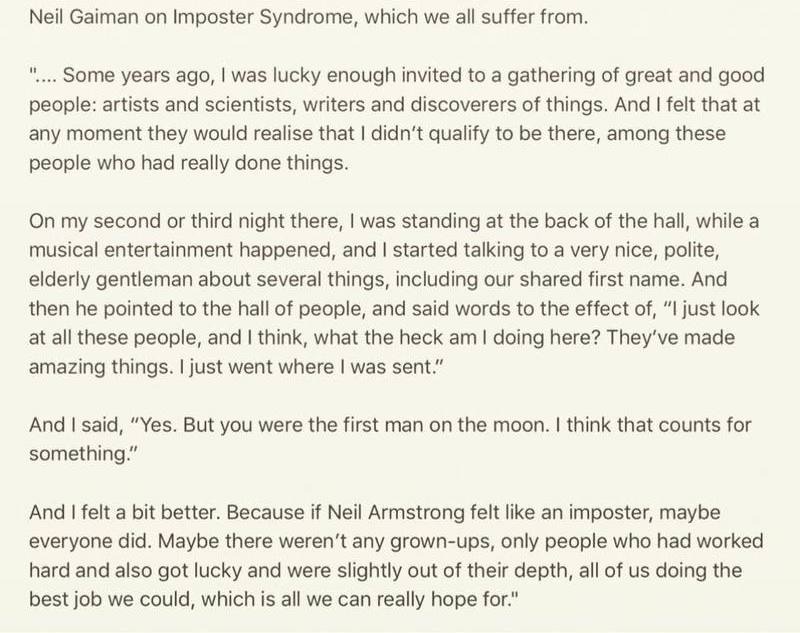

And sometimes we are just awed by the company in which we find ourselves.

We see people of the Neils’ stature as their achievements. We don’t see the incredible cost they’ve accrued to get there. We don’t know how their home town responded to their ambition. We don’t know how their family felt about them leaving. We don’t know how many early mornings or sleepless nights or missed parties there have been. We don’t know how many other opportunities they have sacrificed to get to where they got to.

But those are the struggles we face day-to-day. Our inner monologue of doubts and insecurity is, thankfully, private. But so is everybody else’s.

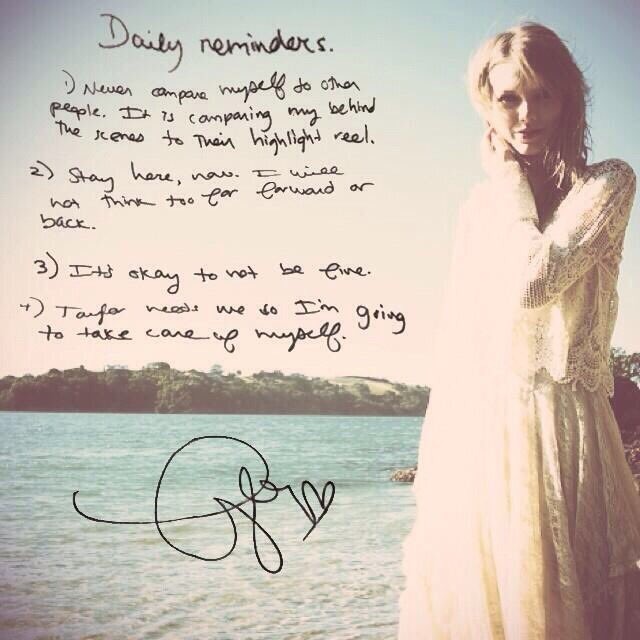

Oh, and if you think not everyone needs a reminder – this is a private note one Taylor Swift wrote to herself while she was on the RED tour (it did well).

Each of us get to choose how much, if any, of it we share with each other. I’d be hard-pressed to find any creative who doesn’t have inertia to share their work. Austin Klein wrote a book about it. You should read that one too, it’s called Show Your Work. It’s also a quick read, but an incredibly valuable one.

I think we don’t want to share our work for two reasons. Because what if it’s shit, that would be embarrassing. Right? But. But, also – what if it’s good?

It’s way scarier if it’s good. If it’s shit, you can still go down to the pub with your mates and make jokes about it.

If it’s good, you’ve achieved something. You’ve earned somebody’s respect. You’re changing the social order again. There’s resistance there. You might have to move to a bigger city to follow the success. You might go on TV. You might get more money than your peers you’ve grown up with all your life. Or more money than your partner. Or parents.

What do you do with that?

Who do you relate to when that happens?

Who’s on your side?

This is why we are afraid. So very afraid. We’re afraid of embarrassment, sure. But we’re even more afraid of being good. Terrified. And being good professionally. Success is scary as fuck.

Because the price we pay for it, is literally everything we’ve ever known.

Should you go for it anyway?

Bukowski really captured the feeling I think

if it doesn't come bursting out of you

in spite of everything,

don't do it.

unless it comes unasked out of your

heart and your mind and your mouth

and your gut,

don't do it.

if you have to sit for hours

staring at your computer screen

or hunched over your

typewriter

searching for words,

don't do it.

if you're doing it for money or

fame,

don't do it.

if you're doing it because you want

women in your bed,

don't do it.

if you have to sit there and

rewrite it again and again,

don't do it.

if it's hard work just thinking about doing it,

don't do it.

if you're trying to write like somebody

else,

forget about it.

if you have to wait for it to roar out of

you,

then wait patiently.

if it never does roar out of you,

do something else.

if you first have to read it to your wife

or your girlfriend or your boyfriend

or your parents or to anybody at all,

you're not ready.

don't be like so many writers,

don't be like so many thousands of

people who call themselves writers,

don't be dull and boring and

pretentious, don't be consumed with self-

love.

the libraries of the world have

yawned themselves to

sleep

over your kind.

don't add to that.

don't do it.

unless it comes out of

your soul like a rocket,

unless being still would

drive you to madness or

suicide or murder,

don't do it.

unless the sun inside you is

burning your gut,

don't do it.

when it is truly time,

and if you have been chosen,

it will do it by

itself and it will keep on doing it

until you die or it dies in you.

there is no other way.

and there never was.

If you are so inclined, I don’t think you have a choice.

But just know, you feel like an imposter, because you are an imposter.

If you’ve ever had a friend lean in and be like "yo. what’s up with this thing that you’re doing?" They’re literally pulling you back into the place they have for you in the social fabric. Note this: not your place. Not where you’re headed.

The place –they– have for you.

Bro, did it ever occur to you, that you’re just maybe way out of your depth?

Being the only woman in a boardroom full of suits is imposing.

Being the only black person in a class full of whites is imposing.

And being the only gay in the village challenges the worldview of that whole village.

And just to make it abundantly clear, you feel like an imposter - because you are. You are breaking the social fabric by being there. You are changing the room.